The baronies of Co. Dublin, 1900. Fingal consists of most of the northernmost five: Balrothery East; Balrothery West; Nethercross; Castleknock and Coolock. Click to zoom. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

So far this blog has focused on the retreat of Irish in South Co. Dublin. This is not by preference; it is because the decline of Irish in the south of the county is much better documented, and includes unequivocal evidence of at least three Irish speakers at Glenasmole in the 1830s, and (possibly) the persistence of vestigial Irish there in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Nevertheless, we do have enough evidence to plot a history of Irish in North Co. Dublin.

Fingallian

Before describing this history, it is important to clarify that the linguistic situation in North Co. Dublin was complicated by the presence of a third language besides Irish and English: Fingallian.

Fingallian was a poorly documented local descendant of Middle English, and appears to have originated in the very earliest English spoken by Anglo-Norman settlers in Co. Dublin; in this and other respects it was substantially identical to the Forth and Bargy dialect spoken in the south of Wexford.

Fingallian was a poorly documented local descendant of Middle English, and appears to have originated in the very earliest English spoken by Anglo-Norman settlers in Co. Dublin; in this and other respects it was substantially identical to the Forth and Bargy dialect spoken in the south of Wexford.

Despite pressure at first from Irish (from which, like the dialect of Forth and Bargy, it borrowed a number of words; see below), Fingallian survived as a curious, precarious linguistic island in North Co. Dublin until the mid-nineteenth century, when it eventually succumbed to local English.

Unfortunately we have so little information on Fingallian that we do not know exactly how far its area of use extended or how this area then contracted. Its name and existing texts suggest it was spoken north of the city in the 1600s and 1700s; its influence is certainly detectable in the nineteenth century English of Oldtown, Co. Dublin, recounted in Patrick Archer's Humours of Shanwalla (1906) here; remnants of it are perhaps also just noticeable in the twentieth century English of Swords, Lusk, Rush, Skerries, Naul et al.

Irish loanwords in Fingallian

Irish loanwords in Fingallian are of particular interest to us; they must have been borrowed directly from the local Irish dialect then spoken in North Co. Dublin. (We have no direct information on whether or not Fingallian speakers also knew Irish; but given the extensive nature of borrowings from Irish - which mirror the pervasive English we find in the Irish of today - a situation where Fingalian was a minority language surrounded by and under pressure from Irish, and where the two languages were used indifferently by bilingual speakers, seems most likely.)

The following short example, from John Dunton's Teague Land, or, a Merry Ramble to the Wild Irish: Letters from Ireland (1698), contains three loanwords from Irish and a name in Irish vocative case with Irish dimunitive (in italics). It is a caoineadh (funeral lament) from a mother to her fisherman son, Robin:

Ribbeen a roon

Ribbeen moorneeng

Thoo ware good for loand stroand and mounteen

For rig a tool and roast a whiteen

Reddy tha taakle

Gather tha baarnacks

Drink a grote at Nauny Hapennys

"Ribbeen a roon" is Irish < (a) Roibín a rúin, 'Robin O sweetheart'; "Ribbeen moorneeng" is < (a) Roibín (a) mhúirnín, 'Robin darling' (the vocative case is curiously missing from the personal name and moorneeng). Baarnack < bairneach, literally 'limpet', was a nickname in Irish for coastal folk (Dinneen, p. 73); thus "gather tha baarnacks / Drink a grote at Nauny Hapennys" means 'gather all the fisherfolk [that knew you], that they can drink to your memory (at Nauny Hapenny's tavern)'. In addition, whiteen < faoitín is a loanword from Irish, but the Irish word is in fact in turn originally a borrowing of English 'whiting'.

While Fingallian is generally outside of the scope of this blog, I will return to the importance of loanwords from local Irish in Fingallian - including further examples - in later posts.

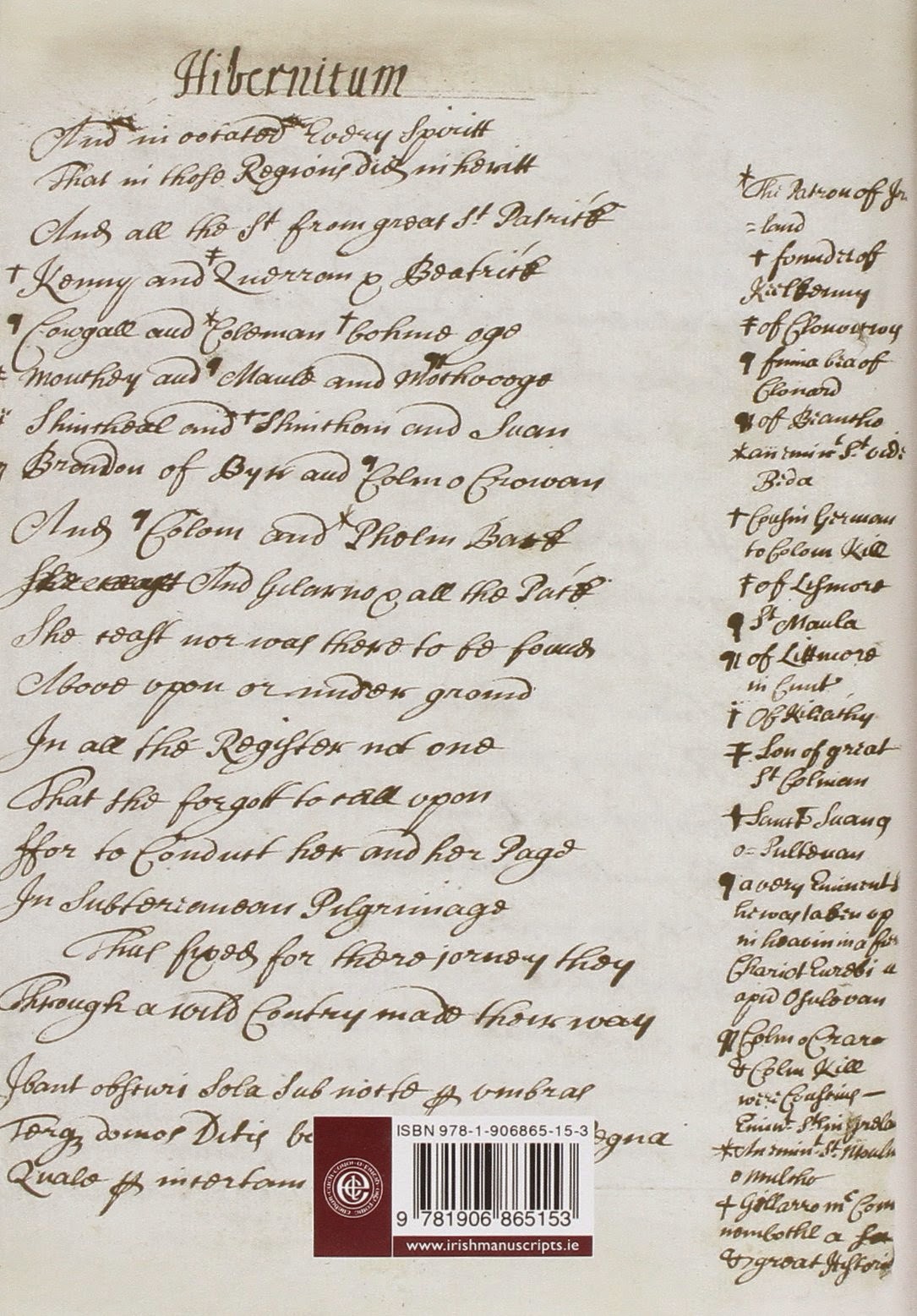

Back cover of Carpenter, Andrew (ed.) Verse Travesty in Restoration Ireland: 'Purgatorium Hibernicum', with 'The Fingallian Travesty' (Irish Manuscripts Commission, 2013) - a fine overview of texts relating to Fingallian.

So how exactly did Irish die out in North Co. Dublin?

Sudden change: the beginning of the decline of Irish

What happened to Irish in North Co. Dublin?

If we consider as a general model the process of language death that took place at Glenasmole in the second half of the nineteenth century (i.e., Irish monoglots to bilinguals to passive bilinguals to English monoglots within a period of about sixty years), we can draw some tentative conclusions for Fingal based on the information above.

In order for Irish to only be remembered by residual elderly bilinguals in Stamullin in 1893, the last generation to have Irish as its native, normative preferred language in North Co. Dublin must have been born near Stamullin around 1773. This in turn means that Irish ceased to be passed on there, with the usual exceptions, by around 1830. This allows for Irish speakers to be found in relative abundance by the Ordnance Survey of that decade, but they would have belonged to the older age groups - the younger people having gone over to English among themselves and only using Irish to communicate with their elders.

The switch from Irish as community language to English in Stamullin therefore took place just slightly over a generation earlier than at Glenasmole (this would help explain the low returns in the language question on the 1851 census: by 1851, English had been the predominant language of Stamullin for at least a generation).

The Glenasmole transmission model also suggests - if Catherine Kirwan really was an exception and that her Irish was "very little" as Mr. Ward protested - that, despite Piatt's assertion of Naul being the last area locally where it was spoken, Irish in fact passed away as the everyday language in Naul a little earlier than at Stamullin (around 1820).

Using the same method, we can extrapolate that Skerries, Rush, Portrane - the fishing village coast - probably ceased passing on their Irish relatively early, around 1790. This would also explain the sudden preponderance of Anglo-Irish terms and English found by Rutty in the fishing villages: the first truly bilingual generation on the Fingal coast would probably have appeared around 1750 (or likely even a little earlier), at coincidentally about the time Rutty was collecting his botanical information. Certainly the coastal villages succumbed to English much earlier than the interior; why this should be so is puzzling, unless their commercial relationship with the rapidly anglicising Dublin city is the primary culprit.

Likewise, extrapolating even further, we can conclude that local Irish likely ceased to be the community language of rural areas around Balbriggan by about 1810. What caused this rapid abandonment of traditional speech in Fingal remains unclear, but it is worth nothing that, of the Fingal areas listed, Stamullin was situated closest to other surviving Irish-speaking areas (in Meath) - for instance Julianstown, which still had a residual Irish-speaking community around 1900 according to Piatt.

The effect of local Irish on Fingallian above shows that Fingal - like Dublin city and elsewhere in Co. Dublin (see here for more information) - was a place where Irish and English co-existed, quite possibly in that order of precedence, for some centuries.

If we consider the evidence in chronological order: Maighréad Ní Mhurchadha (2005, p. 115-120) demonstrates that Gaelic surnames comprised majorities in at least half of the parishes of North Co. Dublin in 1665, and significant minorities in the rest. Old English surnames comprised much of the remainder. Both groups had, at the time, a propensity to be Irish-speaking.

If we consider the evidence in chronological order: Maighréad Ní Mhurchadha (2005, p. 115-120) demonstrates that Gaelic surnames comprised majorities in at least half of the parishes of North Co. Dublin in 1665, and significant minorities in the rest. Old English surnames comprised much of the remainder. Both groups had, at the time, a propensity to be Irish-speaking.

At a more local level, Piatt (1933, p. 6) reports that Finglas was Irish-speaking in 1690, while in 1694 the Howth-Portmarnock area was sufficiently Irish-speaking as to be able to readily provide Irish-speaking crews to passing ships. These were at the time, we should stress, predominantly Irish-speaking areas at their peak - fíor-Ghaeltachtaí - not remnant areas where Irish had otherwise died out or was even close to dying out.

We then learn of Richard Tipper (fl. 1709-1742; note the New English surname) of Mitchelstown near modern Blanchardstown in Fingal, a noted Gaelic scholar, scribe and member of the classical intellectual circle surrounding Liberties (South Co. Dublin)-born Tadhg Ó Neachtain (1670-1749). There is no evidence to suggest Tipper was unusual in being an Irish speaker in Mitchelstown at this time; indeed, as a classical scribe he was quite literally an Irish speaker par excellence.

So far, we see in North Co. Dublin a repetition of the pattern elsewhere in the county between 1600 and 1700: Irish is holding its own, spoken and understood not only by the poor but also by the rich. Those of Gaelic Irish origin, of Old English origin and even those of New English stock all seem to know it well. English also seems well known, although not presumably by the peasantry. It is impossible to say how widespread Fingallian was; but the scanty evidence suggests that wherever it was spoken (fishing villages and the countryside), it was spoken alongside Irish.

So far, we see in North Co. Dublin a repetition of the pattern elsewhere in the county between 1600 and 1700: Irish is holding its own, spoken and understood not only by the poor but also by the rich. Those of Gaelic Irish origin, of Old English origin and even those of New English stock all seem to know it well. English also seems well known, although not presumably by the peasantry. It is impossible to say how widespread Fingallian was; but the scanty evidence suggests that wherever it was spoken (fishing villages and the countryside), it was spoken alongside Irish.

Sudden change: the beginning of the decline of Irish

After approximately 1750, however, evidence for Irish-speaking in North Co. Dublin begins to appear very mixed. For instance, John Rutty's hobby botanical survey of the entire area makes intermittent (if desultory) note of local Irish words, but is oddly silent on the extent of local Irish-speaking. Most tellingly, Rutty reports both Irish and English terms used by the fisherfolk of Skerries, Rush and Portrane: some of the terms are clearly corrupt Irish, others perfectly good Irish, still others very colloquial English - all current in, as Rutty puts it, "vulgar" use. It is thus clear that by the time Rutty is writing (his information is from 1758-1764 but was published in 1772) English is making significant inroads into a traditionally Irish-speaking area, although it is unclear the extent to which Irish or English is the predominant language; the evidence I have supports both conclusions.

We then find that data for 1771 - extrapolated backwards from responses to the language question from those over 60 years of age in the 1851 census in Fitzgerald (1984), p. 130 - show minimum Irish-speaking levels in North Co. Dublin of between four per cent (baronies of Nethercross, Coolock) and 12 per cent (Castleknock). These seem extremely low, but are perhaps evidence of an elderly cohort that had by 1851 long since ceased to consider Irish its everyday language, making backwards extrapolations misrepresentative (see below).

What is abundantly clear in North Co. Dublin is that (as elsewhere in Greater Dublin) between 1700 and 1800 Irish declined swiftly, and to a large extent very mysteriously. In North Dublin as in South Dublin, Irish-speaking communities receded as quickly as an ink blot on paper, shying further and further away from Dublin city.

The nineteenth century

The nineteenth century

By the early nineteenth century English seems essentially ascendant in Fingal; we are thus forced to search for remnant Irish-speaking pockets. Irish was widely spoken at Stamullin townland in the far north of the county (directly adjacent to Stamullen in Meath; the river Delvin cuts between the two and forms the county border) at the time of the Ordnance Survey letters (1836); according to Piatt (1933, p. 29), old people in the Stamullin area still had Irish of some sort - most probably residual passive bilinguals - as late as 1893. Yet Piatt considers that the final stronghold of Irish in North Co. Dublin - 1899 - was in fact to be found about seven kilometres to the west at (the) Naul, also on the Meath border (ibid.):

Tradition has it that the Naul area, just west of Balbriggan, preserved Irish until very recently, a family of Kirwans, locally "Karvan," being said to be the last speakers, though Mr. A. Ward disputes the claim of Catherine Karvan, who died about 1899, to have known more than "very little" Irish.

What happened to Irish in North Co. Dublin?

If we consider as a general model the process of language death that took place at Glenasmole in the second half of the nineteenth century (i.e., Irish monoglots to bilinguals to passive bilinguals to English monoglots within a period of about sixty years), we can draw some tentative conclusions for Fingal based on the information above.

In order for Irish to only be remembered by residual elderly bilinguals in Stamullin in 1893, the last generation to have Irish as its native, normative preferred language in North Co. Dublin must have been born near Stamullin around 1773. This in turn means that Irish ceased to be passed on there, with the usual exceptions, by around 1830. This allows for Irish speakers to be found in relative abundance by the Ordnance Survey of that decade, but they would have belonged to the older age groups - the younger people having gone over to English among themselves and only using Irish to communicate with their elders.

The switch from Irish as community language to English in Stamullin therefore took place just slightly over a generation earlier than at Glenasmole (this would help explain the low returns in the language question on the 1851 census: by 1851, English had been the predominant language of Stamullin for at least a generation).

The Glenasmole transmission model also suggests - if Catherine Kirwan really was an exception and that her Irish was "very little" as Mr. Ward protested - that, despite Piatt's assertion of Naul being the last area locally where it was spoken, Irish in fact passed away as the everyday language in Naul a little earlier than at Stamullin (around 1820).

Using the same method, we can extrapolate that Skerries, Rush, Portrane - the fishing village coast - probably ceased passing on their Irish relatively early, around 1790. This would also explain the sudden preponderance of Anglo-Irish terms and English found by Rutty in the fishing villages: the first truly bilingual generation on the Fingal coast would probably have appeared around 1750 (or likely even a little earlier), at coincidentally about the time Rutty was collecting his botanical information. Certainly the coastal villages succumbed to English much earlier than the interior; why this should be so is puzzling, unless their commercial relationship with the rapidly anglicising Dublin city is the primary culprit.

Howth, 1792. By this point in time, the people shown here probably preferred to speak English, though some of them likely knew Irish.

Farmland meets the Irish Sea near Balbriggan, Fingal. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Postscript: the forgotten local Irish of North Co. Dublin

Irish had ceased to be the majority community language of any place in North Co. Dublin by 1830; even isolated semi-speakers are not recorded after 1893-1899.

As elsewhere, a significant amount of local Irish words survived in some fashion in the Anglo-Irish dialect of Fingal; yet, as elsewhere, no sound recordings were made and no texts of any kind were taken down in the Gaelic dialect of Fingal while it was alive.

Put simply, the local Irish dialect(s) of North Co. Dublin was ignored by observers in its lifetime, and it has remained sadly ignored in death.

As elsewhere, a significant amount of local Irish words survived in some fashion in the Anglo-Irish dialect of Fingal; yet, as elsewhere, no sound recordings were made and no texts of any kind were taken down in the Gaelic dialect of Fingal while it was alive.

Put simply, the local Irish dialect(s) of North Co. Dublin was ignored by observers in its lifetime, and it has remained sadly ignored in death.

B'fhiú an tagairt seo d'fhocal Gaeilge ag mná Ráth Eanaigh/Chill Bharróg as Teistíochtaí 1641 a lua anseo:

ReplyDelete'Hee allsoe saith that in the way as he came by the sea syde from Howth to Dublin, with his Company being about 13teene all on foote saue his wife and haueing their goods at their backs and vppon one Carre, there were many of the women of the villages thereabouts gathering Cockles (as vsually they doe) who shouted aloud sayeing "Siggy Sassinagh, Siggy en Sassinagh", that is "there comes English", which this deponent conceiveth was to sett on the people in armes.'

—Edward Leech, Márta 1643 (BÁC 810 245r)

Litriú Béarla ar "Seo chugaibh (an) Sasanach" atá anseo, b'fhéidir, ón gcomhthéacs (tá an finné ag tabhairt le fios go raibh na mná ag glaoch ar fhir na háite chun tabhairt faoi féin is a mhuintir).

Tá an fuaimniú Seo chugaibh > *Siugaí spéisiúil, más ea. (Féach nach i gcónaí a dhéantaí sh- de s- caol na Gaeilge i litriú Béarla na linne sin.)

Go raibh míle maith agat as do bharúil.

ReplyDeleteIs an-thábhachtach an téacs (agus an comhthéacs agus an dáta) seo. Chonaic mé é cheana féin i leabhar Ní Mhurchadha: Fingal 1603-60: Contending Neighbours in North Dublin (2005, p. 129). (Leabhar ar feabhas agus foinse bunriachtanach má tá aon speis ar Fhine Gall agat.)

Aontaím leat go bhfuil gnéithe eigin áitiúla saoithiúla ann, ach níl a fhios agam go díreach cad atá againn. Mar a dúirt tú, tá Seo chugaibh > *Siugaí íontach aisteach (ach dochúil). Ceist an-spéisiúil is ea í.

Tá "shogh" < seo (le caolú ar an [s] agus [o] soléir, éagsúil le [ə] mar atá sé san suíomh sin go minic inniu) againn as Domhnall Ó Broin ("Donole obreane the Messenger") san Image of Irelande (1581). Ba é an Branach ona Sléibhte o dheas, is cosúil, agus bhí canúint aneas aige.

Tá an -y i "Siggy" [ə~ɛ], b'fhéidir. Feicimid go minic go bhfuil na foircinn "-aigh", "-eadh" srl > [ə] ar fud Sean-Laighin - is eochairghne Laigheanach é, i ndáirire. Agus tá -y ar son -ə i litriú Mhanann agus áiteanna eile freisin.

Seoigí Sasanach ?? cf. amachaigí, amachaí an lae inniu

ReplyDeleteThis blog post provides fascinating insights into the linguistic history of North Co. Dublin.

ReplyDelete